The Good Doctor Jill's Great Professor Sachs

by Sasha Alyson

It was the U.N.’s Millennium Development Goals that had the greatest influence on aid policies in the Global South as the new millennium got underway, but they weren’t widely known to the general public in the West. Far more attention went to a plan that sounded similar but which, despite its high visibility, achieved close to nothing. This was the Millennium Villages Project, which one analysis called “the principal single policy initiative to emerge from the largest-ever gathering of heads of state, the Millennium Summit.”(1)

The founder and head of the MVP was Jeffrey R. Sachs, who brought quite a resume to the job. By age 28 he was a tenured Harvard professor; soon he was advising financially strapped governments on three continents. His prescription: Neoliberal policies of government austerity and a free-market economy. And the change had to be fast: “You can’t jump over a chasm in two leaps,” as he sound-bitingly remarked.

In Russia, however, Sachs’s advice led not to a glorious leap across the chasm, but a disastrous plunge to the bottom – what a Foreign Policy story described twenty years later as “a corrupt, thuggish form of crony capitalism from which the country still has not escaped.”(2)

What went wrong? Sachs largely refused to discuss the subject. When pushed, he claimed that in countries where things had worked out well it was his advice that saved them. Where disaster followed, it was because they hadn’t followed his advice thoroughly enough.

Despite all this, or perhaps because of it, the New York Times Magazine called him “probably the most important economist in the world.” Sachs had a flair for care and feeding of the media. Some years later, while traveling through Uganda with a journalist, he asked to stop the car so he could call his son in the United States. Sachs was wondering how the coriolis effect (you know, the thing about the apparent deflection of a moving object if its frame of reference rotates with respect to an observer) was affected when you crossed the equator. His son was studying earth sciences and might have the answer. Presumably Sachs’s unquenchable curiosity might have waited until he could make the call in private. But Sachs understood that a good journalist doesn’t want to tell that her subject is awesomely bright; she wants to show it with a memorable anecdote.(3)

At this point, we need to ask something — not sarcastically, but as a legitimate question. Media coverage of Sachs consistently described him as “brilliant,” a “wunderkind.” Was his true brilliance in the field of economics? He didn’t understand what caused poverty, he didn’t understand how to end it, he either didn’t know how to conduct a good evaluation or he didn’t want a good evaluation, and he thought aid donors were largely motivated by a genuine desire to help poor people in other countries, rather than by the myriad other interests, mostly leading back to themselves, that are obvious to even a semi-awake observer. Is it possible that Sachs’s true brilliance lay not in economics, but in his ability to manipulate others to describe him as brilliant?

And that, he did brilliantly. Columbia University, eager for a superstar professor, lured him away from Harvard in 2002 with a $300,000 salary, and set him up in an $8 million townhouse from which he could serve as director of Columbia’s Earth Institute. Time magazine put Sachs on its 2004 list of the world’s 100 most influential people, and again in 2005. Bono wrote the foreword for Sachs’s best-selling book The End of Poverty, which proposed that extreme poverty could be eliminated within two decades. Time ran a cover story about his ideas: “How to End Poverty.” Nina Munk wrote a generally flattering profile for Vanity Fair. A Jeffrey Sachs fan club urged him to run for president. MTV filmed a documentary, Angelina Jolie and Dr. Jeffrey Sachs in Africa, in which Jolie introduced him as “the world’s leading expert on extreme poverty.” And then, tragedy struck. Jeffrey Sachs believed it all.

Snarky? Maybe. But true. A belief in one’s greatness can lead to trouble. Does it ever not lead to trouble? For seventy years, “development” is what Europeans and their descendants have said they will provide for everyone else, and no one paying close attention thinks this has gone terribly well for the “everyone else.” Anyone who claims to have the solution needs to take this track record into account. Yet as the MVP launched in 2005, Sachs clearly believed he had the answers, and that other opinions would merely get in the way of progress.

The idea behind the Millennium Villages Project was that a “poverty trap” kept poor countries from achieving their potential. Poor health, lack of capital, illiteracy, hunger, and other factors all interacted. Only a “big push” could overcome this great weight. Left unasked was the question, “In that case, why did the countries that today consider themselves ‘developed’ get where they are without a big push from outside?

Under the Sachs plan, there would be no more scattershot spending. No more trying to improve maternal health in this village, education in that one, and agriculture in a third, this was an integrated development initiative. “In order to make lasting changes in any one sphere of development, we must improve them all,” announced the MVP. The “we,” clearly, was the global North, led by the MVP. The U.N.’s Millennium Development Goals became the official goals of the MVP, which had three partners: The Earth Institute, The United Nations Development Programme, and a newly-formed non-profit, Millennium Promise. George Soros gave valuable momentum with a $50 million contribution.

“[P]eople in the poorest regions of rural Africa can lift themselves out of extreme poverty in five year’s time,” announced the MVP in 2007. It started work in ten countries of sub-Saharan Africa, setting up programs in one or two village clusters per each country. A typical cluster had five to ten villages with a total of around 35,000 people and would receive funding of $120 per inhabitant, per year.

Villages were chosen on the basis of several criteria. Sachs wanted a spectrum of environments and economies ranging from pastoralists to subsistence farming; he also sought villages that were deemed more likely to succeed.

“In five years, not only will extreme poverty be wiped out, Sauri will be on a self-sustaining path to economic growth,” wrote the MVP, referring to the main village featured in the MTV documentary. It sure sounded good. At the end of that video, Angelina Jolie sums up her 2-day visit by assuring viewers that “It is possible to end poverty…. I’m convinced of it, now that I’ve seen this.”

Although presented as a new idea, “Integrated Rural Development” (IRD) had been the big new thing in the 1970s. The World Bank, USAID, Ford Foundation, and Save the Children had funded IRD projects. China tried a 5-year, 1,800-village experiment in the 1990s. The consensus, in the words of a World Bank agricultural expert, was that these programs had virtually no sustainable impact: “IRD failed spectacularly and was completely discredited in the early 1990s.”(4)

Thinking fast, or thinking well

In his influential book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman describes two systems of thinking which co-exist in most of us. System 1 is fast and intuitive. On occasion, this leads to good insights. But quite often, it leads to a bad decision which feels so right, we’re reluctant to look further. System 2 requires more thought. More work. We can’t possibly put this much effort into every decision that comes along, and for many routine items, the speedy System 1 works fine. When the deeper, slower effort of System 2 is needed, we often don’t bother. It’s just too much trouble.

If a difficult question requires too much hard thinking, address an easier, more emotional question instead. That’s one of the many ways described by Kahneman in which System 1 misleads us. To anyone who asked why this case of IRD was truly so different from the past, Sachs would snap back, “children are dying!” By asking “Do we urgently need to do something?” he pushed aside the harder question, “Is this a useful thing to do?”

During its heyday, the MVP became a walking specimen bank for the thinking fallacies described by Kahneman. Putting too much trust in over-confident experts is another easy road to disaster. Kahneman points out that System 1 is eager to place blind faith in anyone said to be an expert — it saves a lot of effort.

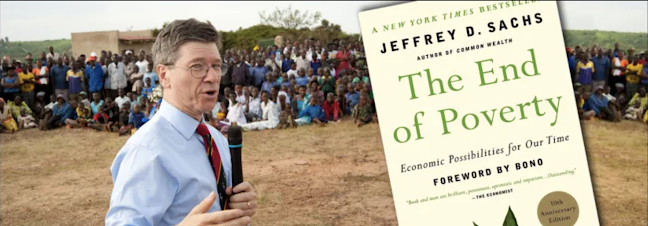

Sachs was dubbed “The Great Professor” and he did his best to reinforce the presumption of his expertise. Many photographs, including one that he featured on his own website in 2012, show Sachs speaking to a rapt African audience. Here is the man with the answers.

If I discussed all the errors Kahneman describes, which were made and encouraged by Sachs and the MVP, I’d be in danger of copyright infringement. But one more must be mentioned: Ignoring the base rate.

For most new proposals, there’s a pool of similar past projects with known outcomes. Those provide the base rate. To predict the success of our new project, we should start with that base rate, then make adjustments – nearly always small adjustments – based on any relevant differences in our new project. But it is human nature to ignore the base rate as soon as we have any information – even irrelevant information – about the new project. We’re eager to believe that “This situation is different.”

At least a dozen Integrated Development Projects had been tried in the past; they all failed. Sachs claimed that this base rate was irrelevant because now there was new technology. But every situation is different. There is always new technology. Sachs was enamoured of technology but never gave a good explanation of just why it would make his new IRD project so different, and in the end, it did not. The base rate of success for previous IRD projects was roughly zero. As it turned out, that was a good predictor of the new one.

Spoiler alert: The Millennium Villages Project was born in a media blitz of headlines, cover stories, and speeches. Less than a decade later it quietly, slowly, slipped from view. The MVP’s failure received far less attention than the great results that were promised.

That failure, if we look at it, sheds much light on the aid industry. Was the MVP a bold plan to help the world’s poorest, as Sachs claimed? Was it one man’s ego-trip — although the critics phrased it more tactfully? Or a new form of colonial relationships, pretending to help the poor? This is the first in a series of stories about Jeffrey Sachs and his Millennium Villages Project, looking behind the curtain to see what we can learn.

Another spoiler alert: The evidence is strong that as far as true goals, helping the world’s poorest was not on the list. Villages in Africa were merely a prop for other goals.

NOTES AND SOURCES

Top Photo: The picture of Sachs speaking to a crowd in Ruhiira, Uganda, is from his website jeffsachs.org. The URL indicates that the photo was posted in January 2012, but the text page is no longer available so I cannot give further source details. It is notable that even at this point, when he could see that the MVP was not achieving what he had promised, this was the image of himself that Sachs wished to project: The American expert, sharing his insight with Africans eager to hear his words.

1. This description is by Michael A. Clemens (Center for Global Development) and Gabriel Demombynes (World Bank) in their 2011 paper “When Does Rigorous Impact Evaluation Make a Difference? The Case of the Millennium Villages.” It’s 56 pages, and the following link will open the PDF: Clemens and Demombynes, Rigorous Impact Evaluation.

2. Paul Starobin, “Does It Take a Village?” in Foreign Policy, 24 June 2013.

3. The journalist was Nina Munk, in her valuable behind-the-scenes book, The Idealist.

4. Clemens and Demombynes present an overview of IRDs in “When Does Rigorous Impact Evaluation Make a Difference?” which is linked above. Victoria Schlesinger also looks at these failures in “Journey to Nowhere,” which appears in Rasna Warah’s anthology about aid Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits. Bill Easterly, a renegade World Bank economist who became a prominent aid critic, in his book The White Man’s Burden thoroughly and clearly documents how ideas such as the “poverty trap” and necessity of a “big push” have repeatedly been trotted out, failed, set aside, then trotted out again a few decades later.

source: Karma Colonialism

Comments